The need to socially move away from others in the time of the pandemic has made me look within. Philosophical though it may sound — much has been said about introspection, from Rumi to Adi Shankara — the truth is that this phase has led to much thinking and analysing, learning and unlearning. I imagined that this would really be the case for most people who are a part of my social world. What are they thinking? How are they coping? How do they energise themselves and deal with the drudgery even as they are cushioned by their privilege?

For many years, my photographic practice has dealt with the central question of how I should or can represent others. So, whether it was the mill workers in Ahmedabad, the Indian Diaspora in England, or the transgender community in Delhi, questioning the idea of the body has been at the root of many of my projects. I am entrenched in, and bothered by, the idea of representation. The camera is an important tool that empowers me to talk about another community — outside of me. My work with the textile mill workers became my first photo book, Working in the Mill No More, with Jan Braman, Oxford University Press and Amsterdam University Press, 2003. I tried to document from 1986 to 2002 and narrate visual stories of migrant workers from across India who had lost their jobs in these mills. Most mills in Ahmedabad were either shut or on the verge of shutting down and thousands of workers were on the road without any social security or job prospects. That was the first time I realised that I need to make sure that they get represented in the true sense.

But then the question of my representing versus the idea of people getting me to represent them is a big one, too. It led me to the Diaspora project where I shot my subjects in frames they had chosen. This was with the Indian Diaspora in England who had migrated from India, Africa, Fiji and so on. The project was shown as an image text exhibition, “Figures, Facts, Feelings — A Direct Diasporic Dialogue” first at the British Council, New Delhi in 2000 and it became a catalogue as well, published by CMAC in 2000, which included important essays on the subject. In this very continuum of representation, my next two projects were with the transgender community from Yamuna Pushta in Delhi and street children from Mangolpuri, a resettlement colony in outskirts of Delhi. I invited my participants to frame, click and narrate their stories — in a sense I was handing over the tool and, therefore, empowering them.

Now, I am left wondering how people engage with spaces, with confinement, with tiring familiarity, a persistent routine what could be a visually compelling idea of the self. Does the idea of representation shift within this context? Does the repetitive dynamic and limited mobility push one to engage with spaces more intimately? In fact, the languor to think about oneself is such a rare occurrence in our otherwise occupied minds and the world. With social distancing as the new normal, suddenly various questions about self, life, and the life around us, etc., which one had always pushed away in the daily rigmarole of life, have come to the forefront.

Sitting at home, I also started wondering about my art/design practice after this lockdown and that got me talking with a few of my friends over several video calls. I decided to work on this project and this seemed like a good timing to ask this question about self. Objects which were gifted, which we inherited, which we collected and bought — all of them are around us. We look at them every day at home but had no time to see them, enjoy them, think about them. As part of this “questioning” or “reflecting”, I conceived this project called “Self Portrait in the time of Social Distancing”, where I invited many of my friends to participate. And now I am looking forward to sharing these powerful image stories with the world at large.

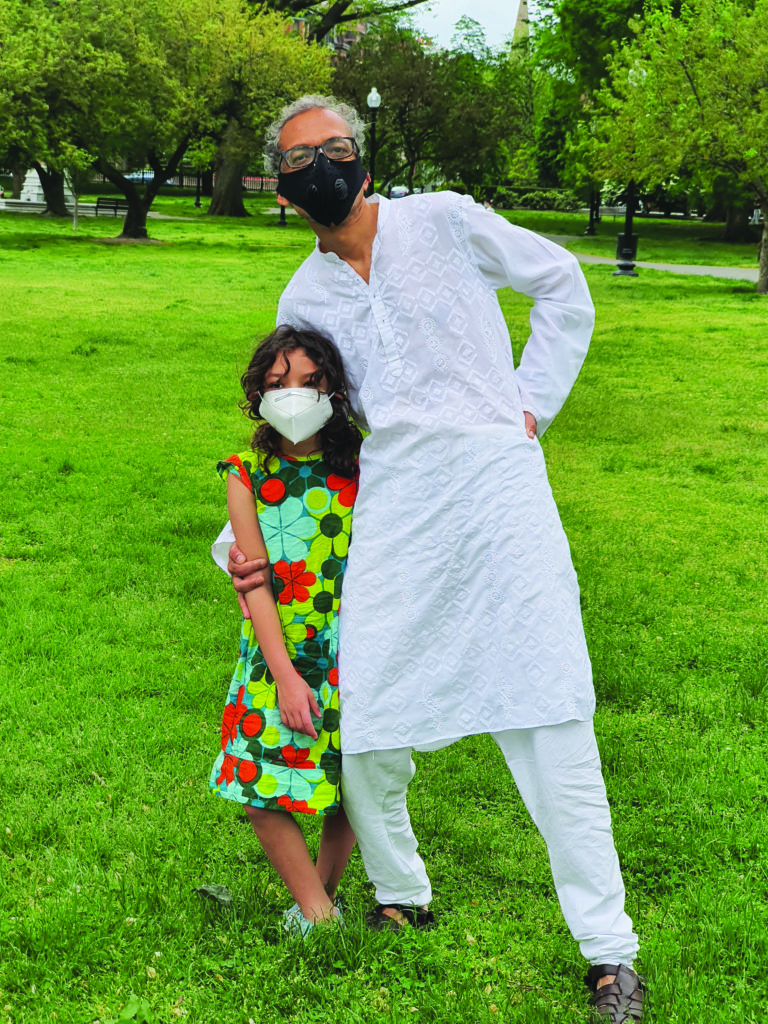

Abhijit Banerjee

I was saying that if this bizarre episode has one saving grace it is that it makes us spend much more time with the kids and because of that, much more time in the parks of Boston. This is really been an life saver for all of us, being close to one of the most beautiful parks in Boston and being able to go there whenever we want, which is often several times a day. It does not take away the sense that we are just marking time, trying as hard as possible to not think about the ways in which our familiar world may be irretrievably lost, but it does return us to the very elemental pleasures of cuddling among the flowers.

Abhijit Vinayak Banerjee is an American economist of Indian origin.